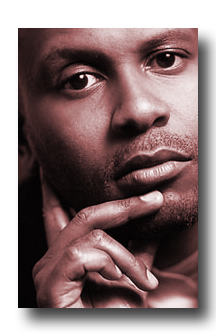

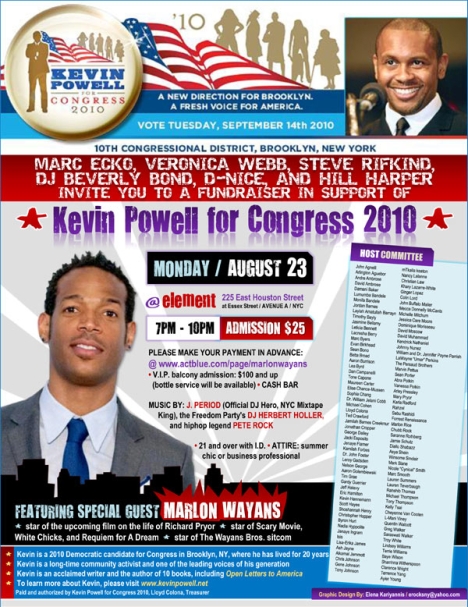

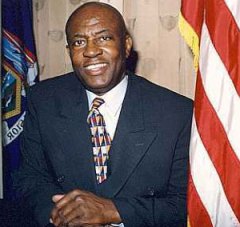

We caught up with long time activist, author and head of BK Nation Kevin Powell. He sat down Hard Knock Radio to weigh in on a number of important topics. We spoke about some of the most recent and disturbing cases of police terrorism and the political, social and economic landscape that has given rise to it..

We spoke at length about the plight of Akai Gurley and the pursuit of justice for him. Powell represented the family of this young father who was gunned down by police as he walked down a darkened staircase in his housing projects. Police claim he was shot by accident. A rookie officer has been charged.

We spoke about the upcoming BK Nation conference scheduled for fall of 2015. We spoke about practical solutions all of us can take to end police violence.

https://soundcloud.com/mrdaveyd/hkr-04-13-15-interview-w-kevin-powell