by Dave ‘Davey D’ Cook (reprint from 1985-The Power of Rap)

Nowadays if you ask most people to give a definition of “rap”, they’re likely to state that it’s the reciting of rhymes to the best of music. It’s a form of expression that finds its roots embedded deep within ancient African culture and oral tradition. Throughout history here in America there has always been some form of verbal acrobatics or jousting involving rhymes within the Afro-American community. Signifying, testifying, Shining of the Titanic, the Dozens, school yard rhymes, prison ‘jail house’ rhymes and double Dutch jump rope‘ rhymes are some of the names and ways that various forms of rap have manifested

Modern day rap music finds its immediate roots in the toasting and dub talk over elements of reggae music. In the early 70’s, a Jamaican dj known as Kool Herc moved from Kingston to NY’s West Bronx. Here, he attempted to incorporate his Jamaican style of dj which involved reciting improvised rhymes over the dub versions of his reggae records. Unfortunately, New Yorkers weren’t into reggae at the time. Thus Kool Herc adapted his style by chanting over the instrumental or percussion sections of the day’s popular songs. Because these breaks were relatively short, he learned to extend them indefinitely by using an audio mixer and two identical records in which he continuously replaced the desired segment.

Modern day rap music finds its immediate roots in the toasting and dub talk over elements of reggae music. In the early 70’s, a Jamaican dj known as Kool Herc moved from Kingston to NY’s West Bronx. Here, he attempted to incorporate his Jamaican style of dj which involved reciting improvised rhymes over the dub versions of his reggae records. Unfortunately, New Yorkers weren’t into reggae at the time. Thus Kool Herc adapted his style by chanting over the instrumental or percussion sections of the day’s popular songs. Because these breaks were relatively short, he learned to extend them indefinitely by using an audio mixer and two identical records in which he continuously replaced the desired segment.

In those early days, young party goers initially recited popular phrases and used the slang of the day. For example, it was fashionable for dj to acknowledge people who were in attendance at a party. These early raps featured someone such as Herc shouting over the instrumental break; ‘Yo this is Kool Herc in the joint-ski saying my mellow-ski Marky D is in the house‘. This would usually evoke a response from the crowd, who began to call out their own names and slogans.

As this phenomenon evolved, the party shouts became more elaborate as dj in an effort to be different, began to incorporate little rhymes-‘Davey D is in the house/An he’ll turn it out without a doubt.’ It wasn’t long before people began drawing upon outdated dozens and school yard rhymes. Many would add a little twist and customize these rhymes to make them suitable for the party environment. At that time rap was not yet known as ‘rap’ but called ‘emceeing‘. With regards to Kool Herc, as he progressed, he eventually turned his attention to the complexities of deejaying and let two friends Coke La Rock and Clark Kent (not Dana Dane’s dj) handle the microphone duties. This was rap music first emcee team. They became known as Kool Herc and the Herculoids.

Rap caught on because it offered young urban New Yorkers a chance to freely express themselves. This was basically the same reason why any of the aforementioned verbal/rhyme games manifested themselves in the past. More importantly, it was an art form accessible to anyone. One didn’t need a lot of money or expensive resources to rhyme. One didn’t have to invest in lessons, or anything like that. Rapping was a verbal skill that could be practiced and honed to perfection at almost anytime.

Rap also became popular because it offered unlimited challenges. There were no real set rules, except to be original and to rhyme on time to the beat of music. Anything was possible. One could make up a rap about the man in the moon or how good his dj was. The ultimate goal was to be perceived as being ‘def (good) by one’s peers. The fact that the praises and positive affirmations a rapper received were on par with any other urban hero (sports star, tough guy, comedian, etc.) was another drawing card.

Finally, rap, because of its inclusive aspects, allowed one to accurately and efficiently inject their personality. If you were laid back, you could rap at a slow pace. If you were hyperactive or a type-A, you could rap at a fast pace. No two people rapped the same, even when reciting the same rhyme. There were many people who would try and emulate someone’s style, but even that was indicative of a particular personality.

Rap continues to be popular among today’s urban youth for the same reasons it was a draw in the early days: it is still an accessible form of self expression capable of eliciting positive affirmation from one’s peers. Because rap has evolved to become such a big business, it has given many the false illusion of being a quick escape from the harshness of inner city life. There are many kids out there under the belief that all they need to do is write a few ‘fresh’ (good) rhymes and they’re off to the good life.

Now, up to this point, all this needs to be understood with regards to Hip Hop. Throughout history, music originating from America’s Black communities has always had an accompanying subculture reflective of the political, social and economic conditions of the time. Rap is no different.

Hip hop is the culture from which rap emerged. Initially it consisted of four main elements; graffiti art, break dancing, deejay (cuttin’ and scratching) and emceeing (rapping). Hip hop is a lifestyle with its own language, style of dress, music and mind set that is continuously evolving. Nowadays because break dancing and graffiti aren’t as prominent the words ‘rap’ and ‘hip hop’ have been used interchangeably. However it should be noted that all aspects of hip hop culture still exists. They’ve just evolved onto new levels.

Hip hop is the culture from which rap emerged. Initially it consisted of four main elements; graffiti art, break dancing, deejay (cuttin’ and scratching) and emceeing (rapping). Hip hop is a lifestyle with its own language, style of dress, music and mind set that is continuously evolving. Nowadays because break dancing and graffiti aren’t as prominent the words ‘rap’ and ‘hip hop’ have been used interchangeably. However it should be noted that all aspects of hip hop culture still exists. They’ve just evolved onto new levels.

Hip hop continues to be a direct response to an older generation’s rejection of the values and needs of young people. Initially all of hip hop’s major facets were forms of self expression. The driving force behind all these activities was people’s desire to be seen and heard. Hip hop came about because of some major format changes that took place within Black radio during the early 70’s. Prior to hip hop, black radio stations played an important role in the community be being a musical and cultural preserver or griot (story teller). It reflected the customs and values of the day in particular communities. It set the tone and created the climate for which people governed their lives as this was a primary source of information and enjoyment. This was particularly true for young people. Interestingly enough, the importance of Black radio and the role djs played within the African American community has been the topic of numerous speeches from some very prominent individuals.

For example in August of ’67, Martin Luther King Jr addressed the Association of Television and Radio Broadcasters. Here he delivered an eloquent speech in which he let it be known that Black radio djs played an intricate part in helping keep the Civil Rights Movement alive. He noted that while television and newspapers were popular and often times more effective mediums, they rarely languaged themselves so that Black folks could relate to them. He basically said Black folks were checking for the radio as their primary source of information.

For example in August of ’67, Martin Luther King Jr addressed the Association of Television and Radio Broadcasters. Here he delivered an eloquent speech in which he let it be known that Black radio djs played an intricate part in helping keep the Civil Rights Movement alive. He noted that while television and newspapers were popular and often times more effective mediums, they rarely languaged themselves so that Black folks could relate to them. He basically said Black folks were checking for the radio as their primary source of information.

In August of 1980 Minister Farrakhon echoed those thoughts when he addressed a body of Black radio djs and programmers at the Jack The Rapper Convention. He warned them to be careful about what they let on the airwaves because of its impact. He got deep and spoke about the radio stations being instruments of mind control and how big companies were going out of their way to hire ‘undignified’ ‘foul’ and ‘dirty’ djs who were no longer being conveyers of good information to the community. To paraphrase him, Farrakhon noted that there was a fear of a dignified djs coming on the airwaves and spreading that dignity to the people he reached. Hence the role radio was playing was beginning to shift…Black radio djs were moving away from being the griots.. Black radio was no longer languaging itself so that both a young and older generation could define and hear themselves reflected in this medium.

Author Nelson George talks extensively about this in his book ‘The Death Of Rhythm And Blues‘. He documented how NY’s Black radio station began to position themselves so they would appeal to a more affluent, older and to a large degree, whiter audience. He pointed out how young people found themselves being excluded especially when bubble gum and Europeanized versions of disco music began to hit the air waves. To many, this style of music lacked soul and to a large degree sounded too formulated and mechanical.

In a recent interview hip hop pioneer Afrika Bambaataa spoke at length how NY began to lose its connection with funk music during this that time. He noted that established rock acts doing generic sounding disco tunes found a home on black radio. Acts like Rod Stewart and the Rolling Stones were cited as examples.

In a recent interview hip hop pioneer Afrika Bambaataa spoke at length how NY began to lose its connection with funk music during this that time. He noted that established rock acts doing generic sounding disco tunes found a home on black radio. Acts like Rod Stewart and the Rolling Stones were cited as examples.

Meanwhile Black artists like James Brown and George Clinton were for the most part unheard on the airwaves. Even the gospel-like soulful disco as defined by the ‘Philly sound’ found itself losing ground. While the stereotype depicted a lot of long haired suburban white kids yelling the infamous slogan ‘disco sucks’, there were large number of young inner city brothers and sisters who were in perfect agreement. With all this happening a void was created and hip hop filled it… Point blank, hip hop was a direct response to the watered down, Europeanized, disco music that permeated the airwaves..

FYI around the same time hip hop was birthed, House music was evolving among the brothers in Chicago, GoGo music was emerging among the brothers in Washington DC and Black folks in California were getting deep into the funk. If you ask me, it was all a response to disco.

In the early days of hip hop, there were break dance crews who went around challenging each other. Many of these participants were former gang members who found a new activity. Bambataa’s Universal Zulu Nation was one such group. As the scene grew, block parties became popular. It was interesting to note that the music being played during these gigs was stuff not being played on radio. Here James Brown, Sly & Family Stone, Gil Scott Heron and even the Last Poets found a home. Hence a younger generation began building off a musical tradition abandoned by its elders.

Break beats picked up in popularity as emcees sought to rap longer at these parties. It wasn’t long before rappers became the ONLY vocal feature at these parties. A microphone and two turntables was all one used in the beginning. With the exception of some break dancers the overwhelming majority of attendees stood around the roped off area and listened carefully to the emcee. A rapper sought to express himself while executing keen lyrical agility. This was defined by one’s rhyme style, one’s ability to rhyme on beat and the use of clever word play and metaphors.

In the early days rappers flowed on the mic continuously for hours at a time..non stop. Most of the rhymes were pre-written but it was a cardinal sin to recite off a piece of paper at a jam. The early rappers started off just giving shout outs and chants and later incorporated small limricks. Later the rhymes became more elaborate, with choruses like ‘Yes Yes Y’all, Or ‘One Two Y’all To The Beat Y’all being used whenever an emcee needed to gather his wind or think of new rhymes. Most emcess rhymed on a four count as opposed to some of the complex patterns one hears today. However, early rappers took great pains to accomplish the art of showmanship. There was no grabbing of the crotch and pancing around the stage.

Pioneering rapper Mele-Mel in a recent interview pointed out how he and other acts spent long hours reheasing both their rhymes and routines. The name of the game was to get props for rockin’ the house. That meant being entertaining. Remember back in the late 70s early 80s, artists weren’t doing one or two songs and leaving, they were on the mic all night long with folks just standing around watching. Folks had to come with it or be forever dissed.

Before the first rap records were put out (Fat Back Band‘s King Tem III’ and Sugar Hill Gang‘s ‘Rapper Delight’), hip hop culture had gone through several stages. By the late 70’s it seemed like many facets of hip hop would play itself out. Rap for so many people had lost its novelty. For those who were considered the best of the bunch; Afrika Bambaataa, Chief Rocker Busy Bee, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Four (yes initially there were only 4), Grand Wizard Theodore and the Fantastic Romantic Five, Funky Four Plus One More, Crash Crew, Master Don Committee to name a few had reached a pinnacle and were looking for the next plateau. Many of these groups had moved from the ‘two turntables and a microphone stage’ of their career to what many would today consider hype routines. For example all the aforementioned groups had routines where they harmonized. At first folks would do rhymes to the tune of some popular song.

Before the first rap records were put out (Fat Back Band‘s King Tem III’ and Sugar Hill Gang‘s ‘Rapper Delight’), hip hop culture had gone through several stages. By the late 70’s it seemed like many facets of hip hop would play itself out. Rap for so many people had lost its novelty. For those who were considered the best of the bunch; Afrika Bambaataa, Chief Rocker Busy Bee, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Four (yes initially there were only 4), Grand Wizard Theodore and the Fantastic Romantic Five, Funky Four Plus One More, Crash Crew, Master Don Committee to name a few had reached a pinnacle and were looking for the next plateau. Many of these groups had moved from the ‘two turntables and a microphone stage’ of their career to what many would today consider hype routines. For example all the aforementioned groups had routines where they harmonized. At first folks would do rhymes to the tune of some popular song.

The tune to ‘Gilligan’s Island‘ was often used. Or as was the case with the Cold Crush Brothers, the ‘Cats In the Cradle‘ was used in one of their more popular routines. As this ‘flavor of the month’ caught hold, the groups began to develop more elaborate routines. Most notable was GM Flash’s’ Flash Is to The Beat Box‘. All this proceeded ‘harmonizing/hip hop acts like Bel Biv DeVoe by at least 15 years.

The introduction of rap records in the early 80s put a new meaning on hip hop. It also provided participants a new incentive for folks to get busy. Rap records inspired hip hoppers to take it to another level because they now had the opportunity to let the whole world hear their tales. It also offered a possible escape from the ghetto…. But that’s another story..we’ll tell it next time.

written by Dave ‘Davey D’ Cook

c 1985

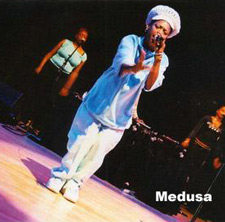

Long before it was acceptable to sing while you rapped, Medusa was out in the fore-front alongside artists like Lauryn Hill,Queen Latifah and the Force MDs who came before them who were paving the way by including harmonies and melodies with their raps and re-introducing that style to the Hip Hop audience.

Long before it was acceptable to sing while you rapped, Medusa was out in the fore-front alongside artists like Lauryn Hill,Queen Latifah and the Force MDs who came before them who were paving the way by including harmonies and melodies with their raps and re-introducing that style to the Hip Hop audience.

Grandmaster Flash

Grandmaster Flash

The Hip-Hop Hypocrisy

“I remember asking my Mom what she did to make pops hate us so much. I couldn’t have been much older than eleven at the time, but I can still remember the anger I felt. Mom broke down into tears and tried to explain it to me, but I couldn’t understand why other kids had their fathers taking them to ball games and stuff, but mine didn’t even take the time to wish me well on my birthday.”

Donald paused a moment to reflect. His expression was a mask of bewilderment and pain. “I used to think that if I could become a good enough kid, it would make my pops want to spend time with me. But the only time my pops really talked to me was when I got into trouble at school. Mom would threaten to send me away to a training school and pops would come over and beat me and lecture me on why I should stop cutting up in class. Many times I would get in trouble just so I could see him and ask him, after he beat me up, if he would come to my basketball game and watch me play. I just wanted him to be proud of me, to love me, but I ended up hating him and everyone around me because he couldn’t.”

When I first heard Donald Williams‘ story, I made a vow to one day tell it to the world. It was a painful tale of a young man attempting to somehow deal with the absence of a responsible father. Donald’s words were filled with rage and interlaced with a venomous sense of hatred. Yet, underneath the anger, there seemed to be a hint of tears. He was in pain, he was hurting, and the man responsible for this devastation didn’t seem to care.

“When I got sentenced to prison, he came here to visit me a few times. He tried to preach to me and counsel me and tell me how wrong I was for selling drugs and living the criminal lifestyle. Man, he even sent me a bible and tried to tell me to give my life to Jesus. But it was too late. After all these years without him, what made this fool feel like he had the right to step into my life now and give out fatherly advice. I would’ve worshiped Satan before I listened to a thing he had to offer. Whenever I looked at him I wanted to just grab his neck and squeeze it and squeeze it and squeeze it until every ounce of his miserable life oozed out of him. I hated that man more than I have ever hated anyone in my life.”

Donald took his father off the visitation list and swore that he never wanted to see the man again. In my presence, Donald never allowed a tear to trail down his chocolate face. But I can imagine those tears came, often, in the middle of the night while contemplating the hate that a father’s neglect created.

Horrific stories of men who refuse to play an important role in the lives of their children are well known. It is an issue that must be dealt with firmly; with serious consequences handed down to offenders. But I am writing this article because I know of another story of blatant child abuse that may hit closer to home than you realize.

It is the story of a child named Hip-Hop.

Afrika Bambaataa

It was born out of raw sense of expression that led many black kids to turn basements and dormitories and bedrooms into impromptu studios. Inner-city geniuses began experimenting with an art form that had the promise of becoming a powerful force in the community. It was fun and competitive. Street corners became the breeding ground for aspiring emcee’s to get their first taste at moving a crowd. With pioneers like Afrika Bambaataa and Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash, along with many others leading the way, rap music exploded into the hearts of young black kids across America.

Along with the birth of Hip-Hop came the emergence of annoyed critics within the older black generation. They wrote Hip-Hop off as a fad that would die out in two or three years. They were far more concerned with stepping across the railroad tracks into the American Dream than paying much attention to the silly Hip-Hop kids with high-top hair cuts who used their mouths to beat-box. (The current Hip-Hop critics who claim to only be against “gangsta rap” are no more than intellectual hypocrites. Vocal members of the older generation disowned rap music even in its infancy – well before it became a vehicle for some artists to disrespect females and illustrate the horrors of street life.)

As a result of the older generation’s neglect, many of Hip-Hop’s leading pioneers ended up signing horrible contracts that gave opportunistic new labels total control over their lives and careers. Instead of influential black leaders using their experience and wisdom to reach back and help Hip-Hop grow into a positive, more focused force in the black community, far too many of these leaders (and rap critics) made the decision to disassociate themselves from the music. Hip-Hop didn’t seem to fit into the cultured, intelligent, and civilized image that they were trying to project to White America.

Still, Hip-Hop grew. Talented poets from all over the country were eager to contribute their vision to the music. Run DMC, LL Cool J, Kool Moe Dee, KRS One, Ice-T, Rakim, and a host of others continued to build upon the foundation of Hip-Hop. Mistakes were made, egos clashed, but rap music followed the beat of it’s own drummer and continued to make huge strides forward. Soon, rap music began reaching the ears of white suburban kids. As a result, Hip-Hop entered the radar screens of white corporate entities as a marketable (and exploitable) commodity. Money was offered, deals were made, and contracts were signed.

Nowhere in this equation did black intellectuals step in to offer guidance and “fatherly” advice. White lawyers in fancy suits shuffled tons of paperwork in front of new artists, enticing them to sign over all their publishing rights for a few pennies. Had more brothers with insight and experience stepped up to the plate to defend the rights of these early artists instead of criticizing them, maybe less rappers would have been raped financially. Tales of bankruptcy and poverty amongst the early innovators of rap music will forever be a footnote in the history of Hip-Hop.

Still, Hip-Hop survived. Though battle-weary and bruised, the music produced prophets who attempted to fill the void left by the older generation. Groups like X-Clan, Public Enemy, and KRS One tried to teach the masses about black power and unity. “Self-Destruction” became an anthem for change as artists from across the spectrum joined together to promote positive interaction. This would have been the perfect time for the intellectual critics of Hip-Hop to reach back and steer rap music onto the Yellow Brick Road to redemption. Instead, these critics turned their backs on Hip-Hop and settled down into their little house on the prairie, beside the Waltons.

Now, in the wake of Tupac and Biggie‘s death, as Hip-Hop struggles to redefine its identity and purpose, there seems to be a resurgence of black critics banging down the door to CNN’s studios hoping to spit out a few intellectual sound bites that will impress their colleagues. Sideline opinions from people who have never even listened to rap music seem to be becoming the norm. More and more black leaders are claiming to be upset that the white corporate structure is exploiting the talents of young black males, and that most artists are too blind to recognize this.

My understanding of history is based more on facts. The truth is, it took white media outlets to embrace Hip-Hop before black-owned media outlets realized that it was “okay” to feature rap groups (the only exception being Soul Train, Ebony, and Jet). It was only after Nike and Reebok and Mountain Dew and Sprite used Hip-Hop artists in high-profile commercials did black-owned companies accept the idea. Quick research will show anyone who is interested that Forbes and Time Magazine had cover stories detailing the economical power of Hip-Hop moguls years before Black Enterprise had the courage to tackle the issue.

Donald Williams wasn’t perfect. Neither is Hip-Hop. They both traveled down a lonely road filled with foolish mistakes and very bad choices. But I understand their anger when, after years of neglect and disappointment, irresponsible father figures tap-dance their way back into the spotlight with two-cent opinions on what the young should and shouldn’t do. The words that Donald said to me, seven years ago, seem to be the same words that many Hip-Hop fans are screaming out today. “After all these years without him, what [makes] this fool feel like he [has] the right to step into my life now and give out fatherly advice.”

Marlon leTerrance is a regular contributer at BlackElectorate.com. As a product of the Hip-Hop Generation’s maverick disregard for conventional thought, Mr. leTerrance writes from the perspective of the “disenfranchised street dwellers, disillusioned by the Struggle”. He can be contacted via e-mail at MarlonLeterrance@aol.com